The Sun is a Workplace Hazard. Why don’t We Treat it Like One?

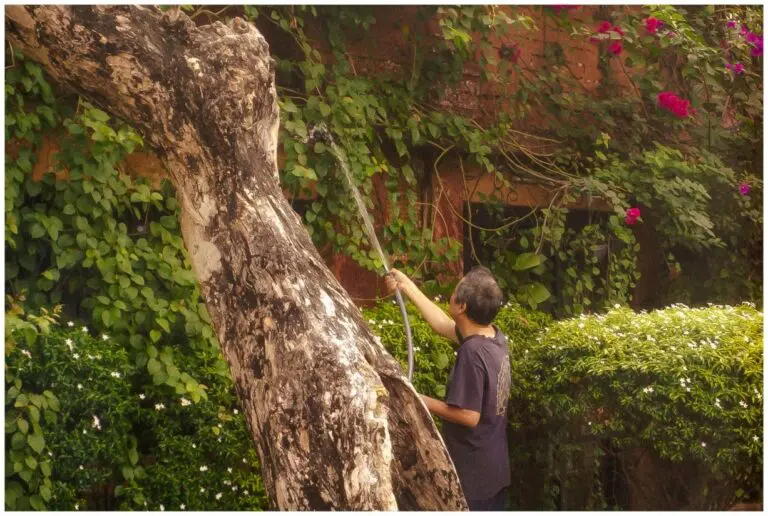

Each summer, outdoor workers across the Western United States begin their day before dawn, preparing to spend 8 to 12 hours under the sun. By noon, the temperatures soar, and by midafternoon, their skin has absorbed hours of continuous ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure, often 10 times more than someone working indoors. However, in the eyes of federal workplace policy, this exposure barely registers.

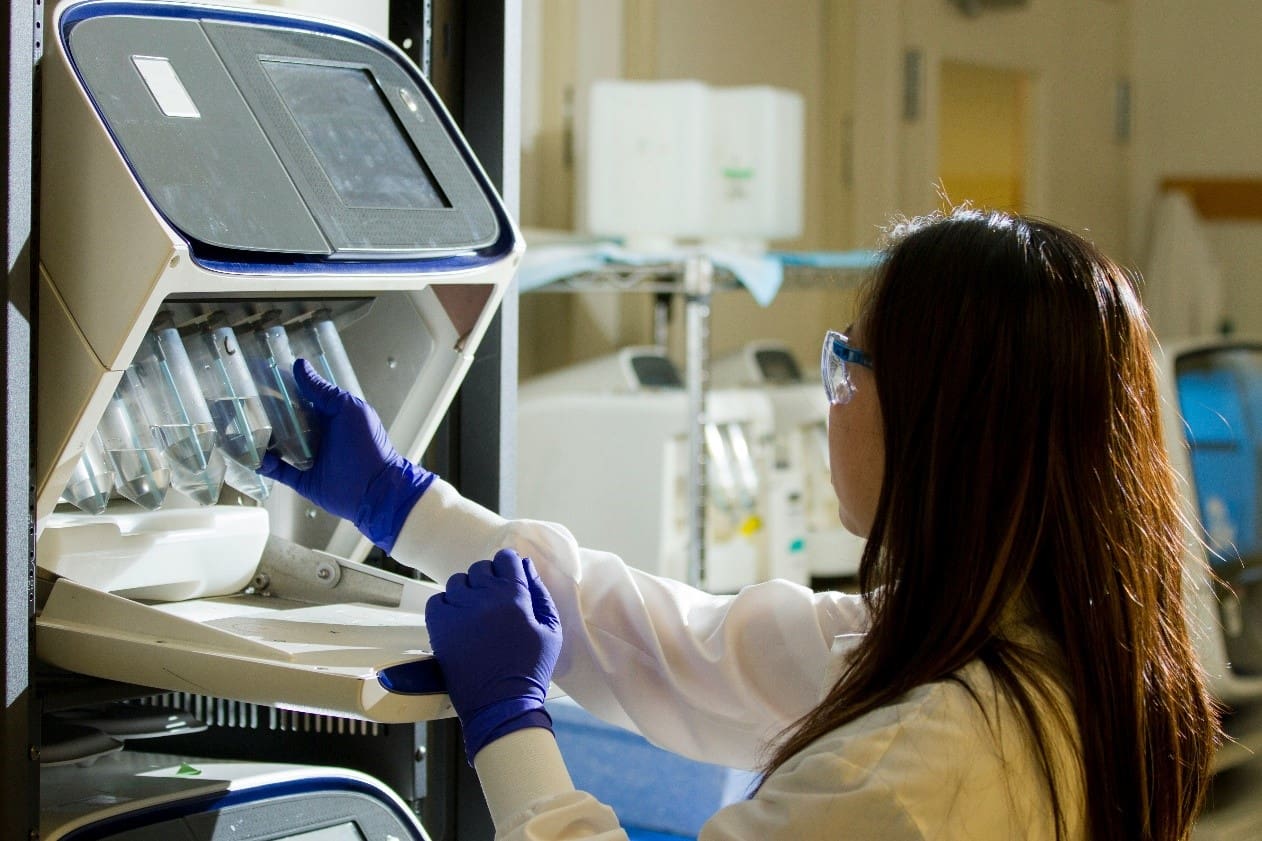

Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States, with more than 5 million new cases diagnosed every year. Ultraviolet radiation is a Group 1 carcinogen—the same category as asbestos, benzene, and tobacco smoke. Yet unlike those, UVR is not treated as a workplace hazard. There is no federal mandate requiring the use of sunscreen, no regulations regarding UV-protective gear, and no obligation for employers to educate their workers about the long-term health risks associated with sun exposure.

Outdoor workers are among those at the highest risk. Studies show that they receive two to eight times the annual UV dose of indoor workers, depending on their geographic location and occupation. In states like California, Arizona, and Nevada, construction and agricultural workers experience cumulative exposure levels that exceed international safety thresholds by early summer. It is estimated that up to 90 percent of non-melanoma skin cancers are caused by UV radiation, and occupational exposure accounts for a significant share of those cases.

We are failing the very people who keep our landscapes green, our buildings rising, and our food supply running, and this is by no means a fringe issue. Millions of Americans work outside, in fields such as agriculture, construction, landscaping, maintenance, and delivery. Outdoor workers face significantly elevated rates of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas, which have been directly linked to cumulative UV exposure. In some cases, the risk is similar to inhaling dust in a mine or fumes in a factory. Nevertheless, only a handful of state-level regulations, most notably those in California, even begin to address the environmental conditions that fuel this exposure.

In countries such as Australia and Germany, UV radiation has been formally recognized as an occupational hazard for years. Employers are required to provide protective gear, sun safety training, and, in some cases, compensation for the treatment of skin cancer resulting from workplace exposure. In the United States, there is no such national framework. Even OSHA, the federal agency responsible for workplace safety, offers only broad language about avoiding “recognized hazards.” When it comes to sun exposure, there is no enforcement, no mandate, and no consistency.

The consequences are predictable and largely avoidable. Outdoor workers in sun-intense states, particularly immigrants, non-English speakers, and low-wage laborers, are routinely left unprotected. These groups are less likely to receive training on sun safety, more likely to experience language barriers, and often lack access to regular medical care. Surveys show that fewer than one in five Latino outdoor workers use sunscreen regularly, despite being at heightened risk.

Some employers offer voluntary protections, such as shade tents, sunscreen dispensers, or hats; however, these efforts are inconsistent at best. Moreover, most workers are unaware that they have the right to request better working conditions.

California’s Cal/OSHA regulations around heat illness prevention require access to shade, water, and rest breaks once temperatures exceed 95°F. Unfortunately, even these standards fail to explicitly address UV exposure, which can cause skin damage at any temperature, even on cloudy days.

Suppose the goal is to reduce preventable cancers in this country. In that case, the focus must start where risk is highest and protections are weakest. OSHA must establish a national standard that recognizes UV radiation as a workplace hazard. Employers should be required to provide sun safety training, protective gear, and access to shade and sunscreen, and ensure that employees are aware of the risks associated with sun exposure. This support must also be available in multiple languages and delivered in ways that reach at-risk communities.

Above all, a cultural shift is needed in how outdoor labor is viewed. Sunscreen and wide-brimmed hats should not be optional extras; they should be treated with the same seriousness as hard hats or harnesses. Furthermore, workers should never feel that asking for protection puts their jobs in jeopardy.

No one should have to choose between a paycheck and their long-term health. The science is precise, the solutions are simple, and the need is urgent. We have regulated chemical exposure, noise levels, and ladder heights to ensure a safe working environment. It is time to add the sun to that list.